I explore how we might develop more inclusive and accessible worship. Drawing on my personal experiences of neurodivergence, I discuss the often overlooked challenges faced by those with hidden disabilities within the church.

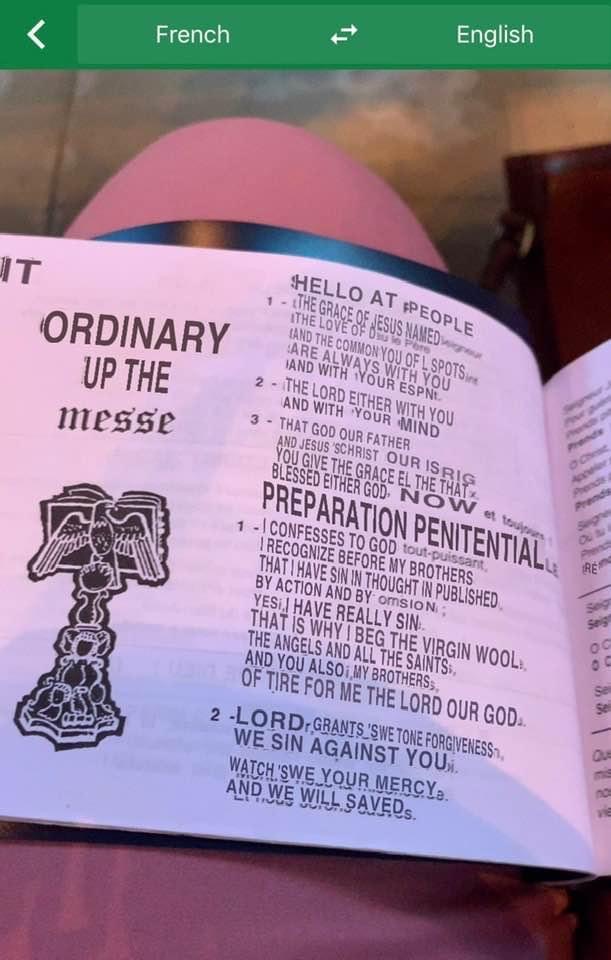

Picture the scene. I’m in France at church at a mass. I don’t have much French, so I get out the camera on my phone to use Google Translate, and point it at the service sheet.

“Yes I have really sin. And that is why I beg the virgin wool”.

Hang on.

Virgin wool? Does Mary knit now? What sort of things does she make – blankets, or maybe something else…?

Where was I? Ah yes, focus, Victoria. You’re meant to be praying, or at least look like you’re praying.

But no. I was lost in translation, and my attention with it.

Barriers to worship

I’m pretty certain I’m not the only one who has these difficulties worshipping, even when we’re worshipping in English. There might be distractions, or we’re tired, or there’s a siren outside.

Usually these barriers are momentary and can be easily forgotten.

But for some, the source of these difficulties aren’t always temporary or easy to forget.

Some of these people might have a disability. But what kind of disability comes to mind when we talk about disability and the church? Something that might require a ramp, or an accessible toilet? Yes, of course!

But what about conditions which are hidden, and aren’t always as tangible or seen? These can include things like visual impairment, hearing impairment, chronic fatigue syndrome or long Covid.

Gifts and challenges of being neurodivergent in worship

It took a diagnosis of ADHD, autistic traits and dyspraxia for me to be able to articulate and appreciate on a fundamental level what I already knew: we’re all a bit odd! All of us, all of us are human, each of us are individually reflecting the gloriously diverse beauty of God.

Neurodivergent folk, like myself, are often highly creative and have unique thinking styles – with the ability to form original connections and observations that otherwise might not be made. This stretches across all domains of life, including how we approach God in our worship. This is as much part of God’s multifaceted and rich nature as our neurotypical peers. But this difference, like other forms of difference, can throw up some challenges in liturgy.

Knowing when to stand or sit can be anxiety-provoking if you’re not been told the rules. Innocuous phrases [in liturgy] such as “we have disfigured your image” might create additional hurdles: my first thought when I hear that phrase, is literally that we’re punching Jesus’ face, and he’s needing a trip to A&E. But the absurdity of that then means that I have to consciously (and in the same way I might with sarcasm or jokes) ask myself: “but is that really actually what was meant?”

A distraction, and another potential barrier to feeling like a full and equal member of the church – and by extension – fully loved by God.

Accessible language benefits all

I work as a senior content designer in the public sector, where my job is to create inclusive and accessible content for the public, such as websites and printed materials. Some of the methods we use are using everyday language and plain English. This benefits everyone, whether they have a disability or not.

Perhaps this is an approach we could draw upon in our own liturgy, so that how we corporately approach God is as open to as many people as possible – both within, and outside, the church – our modern-day equivalent of how even the most marginalized in society met and knew Jesus, and discovered that they too are cherished, valued, and loved by God.

So I’d like to thank the liturgy committee for all the work they’ve done, and looking forward, I’d like all of us as a church, to think about we can creatively think about how we can develop our liturgy to communicate the message of God’s love for all.